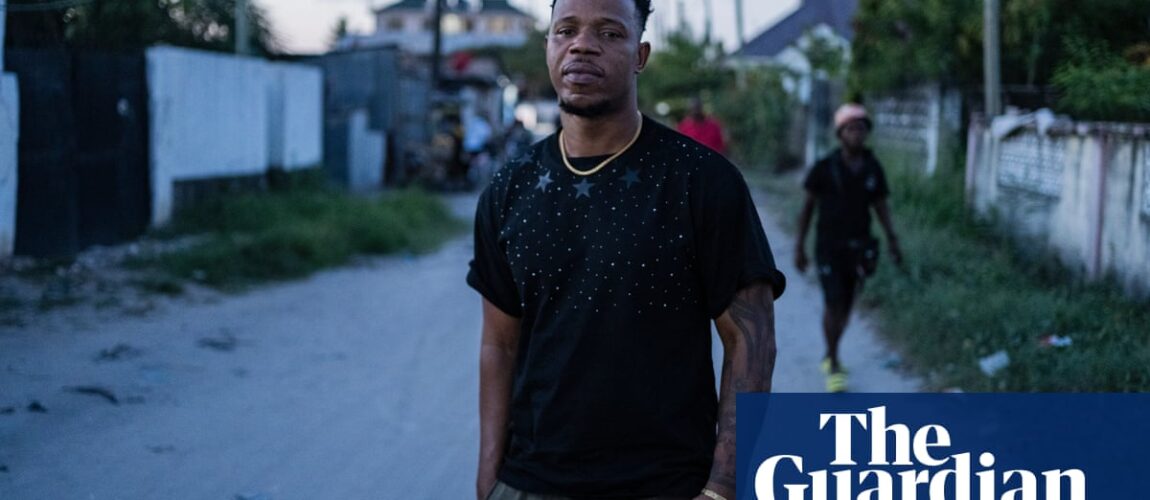

Tanzanian rapper Nay wa Mitego is averse to the thought of the number of times the writer has run afoul of the Tanzanian authorities over his music.

It started in 2016, under the administration of President John Magufuli. Since then, he has faced many challenges, charges, threats and song bans due to music criticism of the government. On one occasion, he spent two nights in prison.

I’ve seen those actions many times that he can’t write, except that he shows that he’s denied permission to hold.

Recently, in September, in the national council of the arts of the country, Basata accused him of four offenses after he released a song called I will say (I will say) about the reported incidents of criticism of the government’s enormity.

“I believe and we have learned that powerful people know how powerful music can be,” Imo, whose real name is Emmanuel Munisi, said in his studio in the commercial capital, Dar es Salaam.

Yes, the career troubles involve the repressive trajectory that Tanzania has been on for almost 10 years. Magufuli has been accused of repressing the opposition, civil society, journalists and other critics throughout the six-year period.

Samia Suluhu Hassan, who succeeded Magufuli upon his death in 2021, initially took a reformist approach to the start of the administration. And recent incidents on his watch – including the disappearances and arrests of government critics and the banning of opposition groups – it means a return to intolerance.

Creative political critics, such as Imo, are among those who have faced retribution under both administrations.

In Nitasema, a fellow Tanzanian artist, Raydiacius, even calls out the brutal kidnappings and murders and says that President Hassan has neglected to deliver on the projects. He raps in Swahili: “Today, you are safe when you leave home/ But you are not safe when you get home/ People are kidnapped, people disappear, people are shot but no one is accused. The one we’re waiting to condemn says it’s a drama / But if your son’s been kidnapped, you dare call it a drama?”

The song accuses the police of being behind the actions.

After his release, Basata leveled four charges against Imo: incitement, misleading the public, releasing the song without the advice of the council, and insulting other nations – Imo compares Tanzania’s situation to those of Rwanda and the DRC.

The work of Immo and other protest artists stands out in the region, where some of the biggest musicians openly support the constitution by performing at party rallies and praising songs for presidents and ruling parties, composing Chama Cha Mapinduzi. In June, Bongo Yellow star Harmonize released Muziki wa Samia (Samia Music), a 10-track album in praise of President Hassan and his leadership.

Growing up in the Manzese neighborhood of Dar es Salaam, Immo started making music in primary school. He made his first demo single, Dala Dala, in 1996 at the age of 10.

He was also a good footballer, and his interest in music created friction between him and his mother, who tried to encourage his education and football ambition, but not rap music, which he felt was “light”, he even said.

Yes, I dropped out in my last year of high school to focus on music. To support himself, he became a barber while making music. In his early years, he made Bongo Flava music, a popular Tanzanian genre that combines hip-hop, R&B and the East African genre of taarab.

In 2010, Imo released his breakthrough song Hello, almost a break. As his popularity grew, he felt a responsibility to make music about social issues. Inspired by his love for Bob Marley, Tupac and Lucky Dube, he ventured into music with social and political messages.

“What they were singing at that time was good, but I read about the history of different countries and their relationships with music and I realized that I could change my community through music,” Imo, 38, said.

Rather, it adds to the political and conscious history of hip-hop in Tanzania, which is tied to the inception of Bongo Flava in the early 1990s with messages of hope for better opportunities for young people after the country emerged from socialism.

For many years, many rappers and other artists, such as Prof Jay (Joseph Haule), Roma Mkatoliki (Ibrahim Mussa) and Vitali Maembe, have mostly freely made music about social ills living in Tanzania.

And the space has been horrified in recent years, with increasing cases of bans, artists, artists, and other acts that create fear and suppress freedom of speech. In 2021, Roma Mkatoliki and three other artists said they were kidnapped from the studio by armed men at gunpoint and tortured.

Nash MC, who started rapping political issues in 2000, said the political scene at that time was not as vibrant as it is now, as strong opposition made people politically aware.

The rapper, whose real name is Mutalemwa Mushumbusi, says hip-hop plays an equally important role.

“Hip-hop began to represent peace, love, unity and happiness.” he said. These are the principles of life.

Indeed, he is popularly known as Rais wa Kitaa (President of the Street), which is also the title of the last album, released in 2022, and released the song in 2021.

His music often features themes of corruption, poor leadership, injustice, poverty and economic challenges. His popular song online, Sauti ya Watu (Voice of the People) released in 2022, tackles unemployment, misuse of funds, and overtaxation, among other problems.

“I’m not afraid of music from any place. And I will continue to criticize everything that is bad,” he said.

Karen Chalamilla, a Dar es Salaam-based cultural writer, said that although Imo has been armed with political themes for many years, increasing restraint people have begun to see the government’s reaction to their music as part of a larger issue of censorship.

“To have someone who points out the truth and to see the treatment that they start because of pointing out the same truth is a lot of vigilance and not complacency,” he said. “It’s a string of events that have made people more fed up.”

Yes, he says that making political music comes with risks – not for two years now, he’s used it partly for security reasons – and pushback, but he doesn’t stop.

“We don’t need to love our country. We need to fight for it, and we need to speak for it,” said the father of three. “Every country has leaders. Being human, they make mistakes. And when they have done it, you must say.