Your support helps us tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to big tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it’s investigating the finances of Elon Musk’s pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, ‘The A Word,’ which shines a light on American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know the importance of analyzing the facts of messaging. .

At such a critical moment in American history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to continue sending journalists to tell both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to block Americans from our reporting and analysis with a paywall. We believe that quality journalism should be available to everyone, and paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes a difference.

Archaeologists they begin to uncover the secrets of a vanished prehistoric land that now lies at the bottom The North Sea.

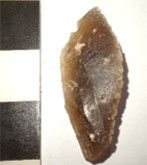

Using special excavators, scientists have just brought to the surface 100 flint artifacts made by Stone Age people between 15,000 and 8,000 years ago.

The artifacts—a series of small flint cutting tools, as well as dozens of flint flakes from tool manufacture—were recovered from the seabed at three different locations on the south shore of the prehistoric wreck.

Each newly discovered ancient site, about 20 meters below the stormy surface of the North Sea, is located next to a series of long-lost estuaries.

The sites – 12 to 15 miles off the Norfolk coast – are expected to yield hundreds more artefacts that will begin to reveal how the people of the lost land lived.

Their economy is thought to have revolved around deer and wild boar hunting and shell collecting. Parts of the North Sea floor are of enormous archaeological importance because they have been relatively untouched by humans since they were submerged between 10,000 and 7,500 years ago.

On land, Neolithic, Bronze Age, Iron Age, Roman, medieval and modern settlements, roads, forestry and agriculture have destroyed vast amounts of early human archaeology.

U Britain 99 percent of the period of human occupation preceded the Neolithic, and later settlement and agriculture. That 99 percent has been partially erased by the recent 1 percent of human prehistory and history.

But on the North Sea floor, post-Stone Age human influence has been greatly reduced, and as a result some Stone Age hunter-gatherer “landscapes” have survived largely intact on the sea floor.

“Our research on the North Sea floor has the potential to transform our understanding of the Stone Age culture in and around what is now Britain and the contiguous continent,” said North Sea Archaeological Survey leader Professor Vince Gaffney of the University of Bradford. Center for Submerged Landscapes.

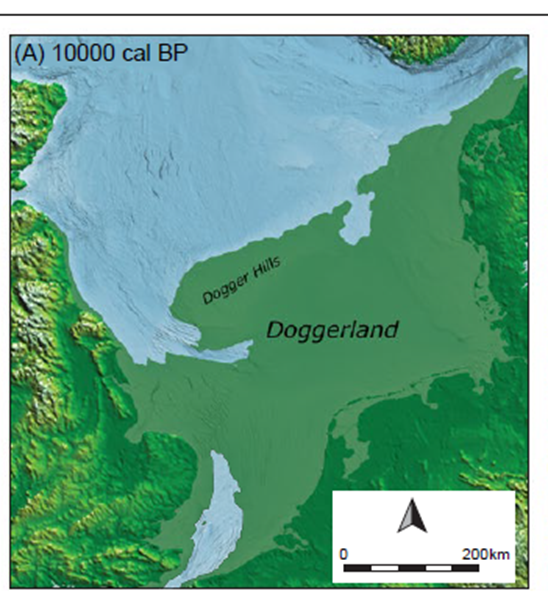

This prehistoric treasure chest hides a tragic story and a warning. In a period of just 1500 years (roughly 8000 BC to 6500 BC), an area almost the size of Britain was swallowed by the sea as a result of rising sea levels caused by an intense period of global warming.

In 8000 BC, about 80,000 square miles of what is now the southern part of the North Sea was dry land. But by 6500 BC only about 5,000 square miles remained.

During that period, an average of 50 square miles of land was lost each year—sometimes much more. As the sea level rose, the Stone Age population, which lived mostly along the coast and thus at altitudes closer to sea level, became more and more vulnerable to seasonal flooding.

As the sea swallowed up the hunting grounds, successive generations of the area’s inhabitants must have been driven from their traditional lands.

Future archaeological work will likely shed light on how this drama unfolded. However, what has happened to Britain’s lost North Sea prehistoric world is a stark warning to 21st century humans about what modern global warming will do to many coastal and lowland communities around the world in the coming decades and centuries.

The ongoing archaeological survey in the North Sea is a joint operation led by the University of Bradford and Belgium’s Flemish Maritime Institute. The research is being undertaken in collaboration with the North Sea Wind Projects and Historic England’s Marine Planning Department.

The drowning of so much Stone Age land by rising sea levels after the Ice Age was a key event in British prehistory – and Britain’s status as an island dates back to that time. The scientists involved in the research believe that in addition to helping us understand the past, their work can also be a warning for the future.

“As we go back in time, we begin to understand more clearly what future sea level rise could do to humanity. Our collaboration with the North Sea wind community is part of Britain’s drive to reach net zero and thus combat global warming,” said Professor Gaffney.