In May 1989, former US president Jimmy Carter he walked into the lobby of a Panamanian hotel and revealed that he was destined to be heard despite the efforts of military leader Gen Manuel Noriega to shut him down.

Carter was still widely despised in his home country, where his reputation as a one-term president in the late 70s was crucified by endless gas lines, Iran’s mocking of the seizure of American hostages and a general perception that he had failed to lead the fight. book of the world

Later, through his myriad works, he won respect for himself Carter Center and his efforts to eradicate great diseases, suppress middle conflicts, and reform inhuman governments. Driven by a deep religious faith and a missionary zeal that others would find grating, he set out to do what he could not do as president – to change the world. It was part of his center that he was an incredible judge of the election of the governments of the governments at the end of the cold war. It was Panama his first.

Noriega was accused of drug trafficking in the US, even though he had worked for the CIA for a long time, and he hoped to ease the pressure on the US with an election that would see a candidate installed.

Carter, alone among former US presidents, had the standing and credibility with Latin Americans to reject proposals or events. To begin with, he signed treaties to hand over the Panama Canal Zone, an American territory at the time, to Panama in 2000 over the strong declarations of Ronald Reagan, who defeated Carter in the 1980 presidential election, and the Republicans in Congress. Donald Trump was now threatening get the back channel.

Carter met Noriega the evening before the military dictator’s schedule. He was a Carter Center assistant with former president Jennie Lincoln. “It was surreal. President Carter was there and Mrs. Carter took notes. I translated Noriega’s Spanish into English for the president,” he said. “President Carter asked Noriega if he would accept the event if it went against him. Noriega was very arrogant and confident that he would be beaten.”

I knew Noriega. His candidate was defeated by the battle. The electoral delegation was made in the dictator’s lap and he tried to fix the issue clumsily. Carter opposed the top officials.

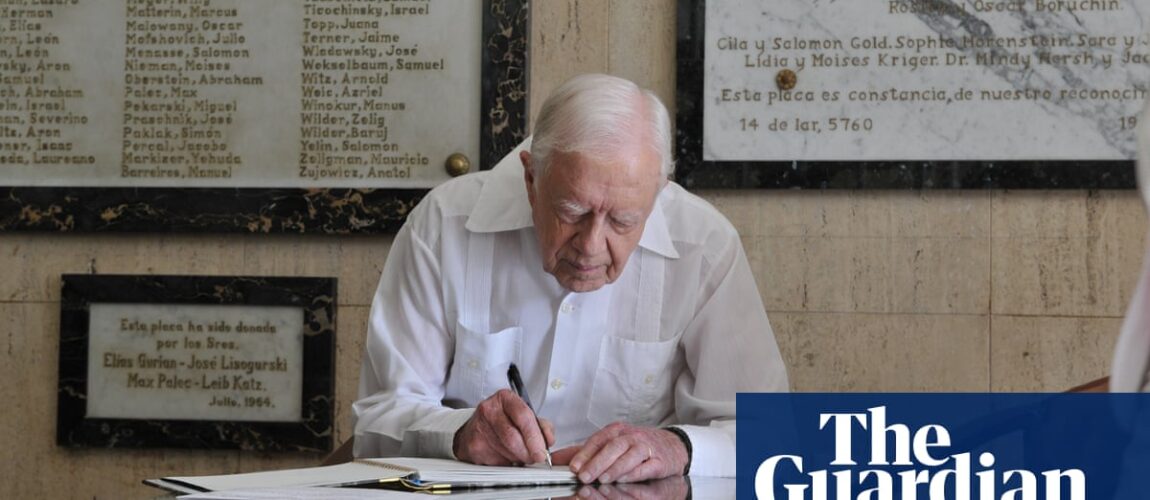

“Are you honest people or are you thieves?” he asked them. The former president tried to see Noriega again, but in vain decided to go public. The electoral commission blocked the media during the press conference, so Carter walked across the street and gave an incorrect address to reporters in the lobby of the Marriott hotel.

As Noriega’s soldiers circled outside, Carter’s Secret Service guards set up two exit routes just in case. “The government is getting elections by fraud,” Carter said. “It’s robbing the people Panama of their legitimate rights. “The election was annulled and by the end of the year the US had invaded and overthrown Noriega, although that is not what Carter would have wanted.

It is difficult to imagine another former US president having the confidence to carry out such a task in the Latin American region. Carter’s record as president in the country was far from untouched, but his administration began an annual report on human rights practices by foreign governments, which led to the end of military aid to five Latin American dictatorships for the rest of his term.

He also pulled the plug on long-standing support for the Somoza regime in Nicaragua, helping to bring about his downfall with the Sandinistas in 1979, though he maintained support for the government in El Salvador despite human rights abuses.

Opinion is divided on the impact of Carter’s policies, which were suspect due to wartime tensions and a long history of US strategic behavior in Latin America. Ordinary Latin Americans, however, noticed that Carter was an interlude from the usual US Swaptor in their country, sharply opposed to those who were elected before and after him.

It was the beginning of Panama. The one-term president who left office was widely derided as weak and incompetent to prove himself more steely and effective outside the White House.

His Carter Center played a major role in the near-eradication of Guinea worm disease and other diseases that have ruined so many lives, as Carter put it, “some of the poor and neglected people on earth.” Carter had a hand in resolving conflicts from Haiti and North Korea to Sudan. His organization has monitored around 100 elections since the first in Panama.

He used the residual authority of the US president, who was able to get on the phone of the White House, to oppose the authoritarians of various quarters, the dictator of Ethiopia, Mengistu Haile Mariam, to the well-known warlord of Liberia and the former president Charles Taylor, now. serving a 50-year prison sentence after being convicted by an international tribunal of terrorism, murder, rape and war crimes. He pushed for human rights issues in Haiti and Cuba. A Quinnipiac Academy poll in November 2015 he declared that American voters thought Carter had done the best job of any president since leaving office.

The Nobel Committee recognized it a few years ago in the peace prize to this rarest of the presidents in 2002, who was found in Vietnam with Habitat for Humanity attached to the poor houses, in which he played the leading role, when tortured in the US prison Guantánamo Bay, Barack Obama strikes a drone or helps Tony Blair for the “abhorrent” invasion of Iraq.

The same moral code or self-righteousness, according to which he describes, the president agrees to support himself in Congress because of his prudent policies on the environment and energy, which he refused to sign more in the pork barrel of the state. in modern times they spoke their minds more freely than the most ancient governors.

Carter said that much of the fierce hostility toward the first African-American president was because of his race. He warned that big money was so pervasive in American politics that the US was “no longer a functioning democracy” because of “unlimited political influence”. He accused the National Rifle Association of influencing “weak politicians” in favor of gun control and railed against the death penalty.

But Carter ran into nothing, as he liked to call it as he saw it Israel.

In 2006, he drew a torrent of criticism and abuse with a book critical of Israel’s failure to end the occupation for peace. The title – Palestine: Peace Not Apartheid – suggests that Israel is pursuing a racist policy against the Palestinians.

A pro-Israel press group took out a full-page ad in the New York Times to demand that the editors correct supposed errors that were not errors at all. Other presidents have announced a peace agreement between Israel and Egypt, which has held up for nearly four decades as antisemites and haters of Israel.

Alan Dershowitz, a leading constitutional lawyer who describes himself as a liberal but has advocated the collective destruction of entire villages as punishment for Palestinian incursions, accused Carter of having “a long, long theological history of anti-Semitism coupled with virulent anti-Israelism.”

Carter angered critics by standing up and taking criticism. He said balanced debate about US policy on Israel is “virtually non-existent” in Congress or in presidential circles, and accused US politics of being a leadership “in the pocket” of the Jewish state.

“We cannot be peacemakers if the leaders of the American government are seen as knee-jerk supporters of all the actions or policies of whatever Israeli government happens to be in power at the time. This is exactly what must be done,” he wrote.

Carter also took on the most powerful American public affairs lobby group Israel Lobby (Aipac), which few American politicians dare to cross, accusing him of “dominant influence” on US policy. In August 2015, he created a new sensation by telling the British magazine Outlook that the then and future prime minister of Israel, Benjamin Netanyahu, he intended not to rule with equal rights for the country of Palestine.

Carter was rightly tested with Netanyahu, who was late said by the international criminal court for the crimes of Gaza, going to war, would openly oppose the state of Palestine.

There is no doubt that Carter’s views on Israel are rooted in his deep Christianity. Some accused him of antisemitic tropes. Whatever he was doing, he wasn’t afraid to show his opinion long before he became president. He first visited Israel in 1973 with the president of Georgia.

In a meeting with the legendary Prime Minister Golda Meir, he decided to give the secular leader of Israel a firmly religious rebuke. “Although I doubted that I had recently taught lessons from the Hebrew Scriptures, and that the usual historical pattern was that Israel was punished whenever the leaders turned away from the pious worship of God,” Carter wrote in vol. “I asked if he was concerned about the secular nature of his Labor government.” Chain smoking Meir lit another cigarette and said he was not.

It seemed natural then when Nelson Mandela asked Carter to become a senior founding member in 2007.

The former South African president said the organization’s former leaders used “almost 1,000 years of collective experience” and political independence – they didn’t have to worry about their votes or laws – to tackle issues they could take on in power and organizations such as the United Nations, from the climate crisis to HIV/AIDS. , but specifically to some of the strongest competitions in the world. Carter joined senior diplomats in Egypt to press then-president Mohamed Morsi for an “inclusive, democratic transition.”

The former US commander has traveled to Burma, Cyprus, the Korean Peninsula and Sudan. But notably, there was no major embassy in Iran. She campaigned for equality for women and girls. Then building houses, giving more talks critical of Israel and, even after his cancer diagnosis, promising that he wouldn’t stop until he couldn’t go any further. Carter is true to his word.