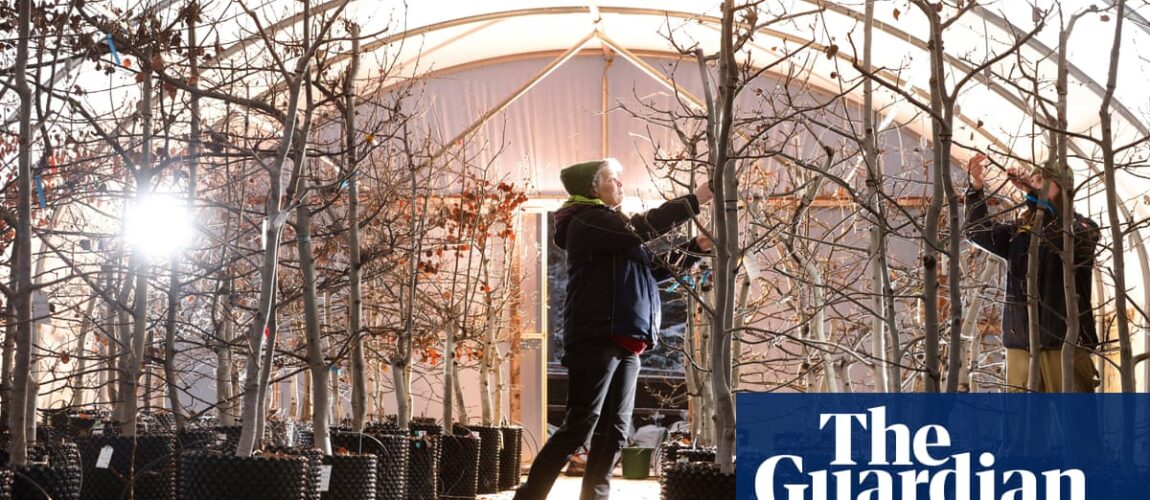

In nature, deep in the Scottish Highlands, there is a polytunnel that dominates a small forest of slender gray aspen trees. It is known as the “tor-chamber”.

Aspen is one of the UK’s rarest but most valuable trees. And to produce small and tender aspen seeds he collects from the charity Trees for Life, these 104 specimens were deliberately made to suffer.

The water may be fast, the limbs may be sheared off, or the trunks may be split and girthed, the bark of the slats rolled or supine. And despite the frost-cold and snow falling outside the tunnel, the buds begin to form a leaf.

It seems paradoxical, but it works: it helps the aspen flower when it is strengthened and produces short seeds that are indestructible.

In a little-understood quirk of nature, UK aspens rarely flower in the wild and rarely cross with each other. He lives most of his life in isolation. They often cling to rocks or rocky slopes to escape the sheep and deer, the male trees being too far away to fertilize the females by nature.

“We treat them with a lot of affection most of the year, but we can see in the wild that they respond to the force of flowering,” said Heather McGowan, a worker at the Unconquerable Trees of Life center at Dundreggan near Loch Ness.

“So, for example, when there was mass flowering in 2019, it was followed by a very hot and dry spring the previous year. We think it’s a stress response.

“And you see if the member is injured then it is going to bloom next year. So again the stress response. We are trying to imitate what makes them in the tunnel under forced pressure.”

Aspen idiosyncrasies have disturbed the population of British forests. Some liken it to a panda: scarcely ferocious, and slow to mate. Like the black and white bear, the aspen has a very narrow window of fecundity, a few weeks each spring.

In Norway, a closer relative of the British, the aspen flowers every year and reproduces quite happily. In the UK, however, a natural source of fertility is such a rare aspen site that it usually spreads by roots, creating large trees derived from a single parent.

While individual aspen bloomed several times, only two flowers appeared in the mass Scotland in the past four decades: in 1996 and 2019. Its seeds are so light and have a minimal length force, it is necessary to be grasped by immediate contact with disturbed ground.

However, the aspen is known as an important species of critical importance for biodiversity. Growing rapidly, the roots and leaves replenish nutrient-poor soil.

McGowan manager Jill Hodge said: “It is one of the trees that benefit the most biodiversity from other species. It is rightly at the top of the list as it is home to rare mosses, lichens, hoverflies, and moths of the darkly woven beauty. It is absolutely amazing for biodiversity and can be used for wood production.

Hodge believes that Scotland’s aspen is losing fertility because of age. Kenny Hay, tree nursery and seed manager for the State Department of Forestry and Land Scotland (FLS), believes that the regular flowering system should stop and instead the answer to their shortage is through careful and self-replicating propagation.

“No one knows for sure,” he said. “But in Scotland we suspect that they were generally forced to plant roots rather than produce seeds.”

Trees of Life is the only tree nursery in Scotland producing aspen seed – other aspens have been born from root cuttings and clones, but efforts to restore the tree are now happening across the UK.

Its bushes are taken away by the FLS and used in private indigenous forestry projects. His progeny were also sent to nurseries at Thetford in Norfolk and Surrey, where they could discover regular flowering in England’s warmer climates.

In Dundreggan and near Loch Affric there are aspen forests. And in the Cairngorms, a major new aspen recovery initiative was launched in early November to help the map and restore it to the wild.

Hay said the final aspen would be so successfully restored that it would spread naturally across Britain for longer grazing. “What we need in the rest of Britain is 200 years of pioneer birch, aspen and dirt only rolling the ground and abandoning it,” he said. “It’s a very long-term project.”