Your support helps us tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to big tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it’s investigating the finances of Elon Musk’s pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, ‘The A Word,’ which shines a light on American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know the importance of analyzing the facts of messaging. .

At such a critical moment in American history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to continue sending journalists to tell both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to block Americans from our reporting and analysis with a paywall. We believe that quality journalism should be available to everyone, and paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes a difference.

The 20-year-old college freshman was still asleep that Sunday morning in the family home on the shores of the Andaman Sea in southern Thailand when her mom, sensing something was wrong, woke her up, saying they had to leave immediately.

That day is forever etched in Neungduangjai Sritrakarn’s memory: December 26, 2004, the day of her fatal Indian Ocean the tsunami hit the south and Southeast Asiaafter a magnitude 9.1 earthquake off the west coast of the Indonesian island of Sumatra.

It was one of the worst natural disasters in modern history.

Neungduangjai’s mom noticed a strange pattern of white caps at sea, just as a relative who had returned from fishing came to warn them. They grabbed all the basic documents of the family members and jumped on the motorbikes.

Within minutes, Neungduangjai, her mother, father, brother and sister were running, trying to get as far away from their village of Ban Nam Khem as possible. Looking back, Neungduangjai saw a wall of water, taller than her home, moving towards the shore in the distance.

She had never seen anything like it.

They were about 3 kilometers (1.8 miles) away when a wall of water crashed onto the coast of Phang Nga province and caught up with them, knocking them off their bikes. The water was dark, washing away all kinds of objects, man-made and natural.

Nuengduangjai pulled herself to her feet, but she could barely stand in the moving mass – the water was almost up to her knees.

At the time, she did not know that the tsunami had hit a dozen countries, leaving about 230,000 dead, about a third of them in Indonesia. About 1.7 million people have been displaced, mostly in the four worst-affected countries: Indonesia, Sri Lanka, India and Thailand.

At least 5,400 people were killed along Thailand’s Andaman coast, and around 3,000 are still missing, according to the Thai government.

The shrimp farm where Neungduangjai’s family worked and lived was wiped out.

In its place today is a thriving bar and restaurant — the fruit of Neungduangjai’s rebuilding efforts — with a porch overlooking the beautiful sea. The view she said wouldn’t have been there if it hadn’t been for the tsunami that destroyed parts of the coast.

In Phang Nga, life has been restored and tourists have returned – on the surface, all is well.

Neungduangjai, who was home from studying in Bangkok for the New Year break when the tsunami hit, said her immediate family survived but lost five relatives, including her grandparents. One of her uncles was never found.

After a week of staying with relatives in the nearby province of Ranong, she returned. She remembers the stench of death and how she thought everything had been moved from its original place.

“There were bodies everywhere,” she said. “When I returned to the village, I could not recognize a single thing. … Everything was different.”

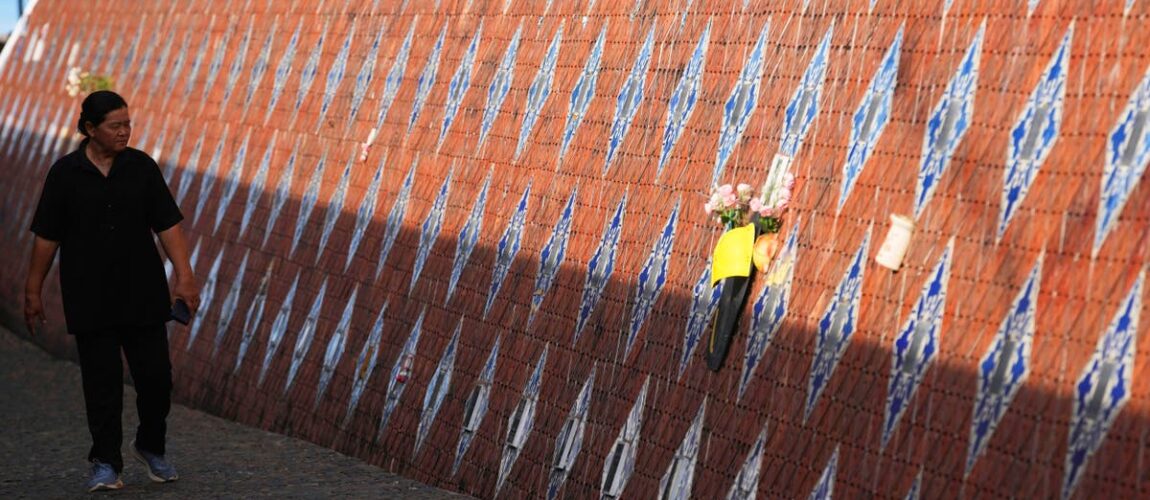

Although tourists have little reason to notice them, reminders of the tragedy abound in Phang Nga today – signs showing the evacuation route, tsunami shelters near the beaches, several monuments and museums displaying the wreckage and photographs that tell the story of that day.

Sanya Kongma, assistant village head of Ban Nam Khem, said that development has come a long way and the quality of life in the village is good compared to 20 years ago.

But the haunting memories and trauma of what they went through are very present and fear is never far away, he said.

“Even now… if there’s a government announcement on TV, or whatever, that there’s an earthquake in Sumatra, everyone will be scared,” he said.

About once a year, the siren sounds in a tsunami evacuation drill. But what should reassure residents of their safety may lead some survivors to relive their pain.

Somneuk Chuaykerd lost one of her young sons in the tsunami while she was at sea, fishing with her husband.

The 50-year-old still lives in the same place, the sea in her yard. In evacuation drills, she learned to hold an emergency bag with all important documents. The bag is in her bedroom, along with a photo of the boy she lost.

But the siren freezes her every time and makes her heart beat faster. “I don’t know what to do. I don’t know what to grab,” she says. “It’s so scary.”

But she has come to terms with the tragedy and has no plans to move away.

“I live by the sea. This is my life. I have nowhere else to go,” she said.

As for Nuengduangjai, for years after the tsunami, every time she looked at the sea she would have a panic attack. In her sleep, she was haunted by the roar of the waves.

She chose to return home after college and earn a living right by the sea. She is proud of her bar and restaurant.

“I’m still scared, but I have to live with it, because it’s my home,” she said. “Some have moved away, but I haven’t. I’m still here.”