Your support helps us tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to big tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it’s investigating the finances of Elon Musk’s pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, ‘The A Word,’ which shines a light on American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know the importance of analyzing the facts of messaging. .

At such a critical moment in American history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to continue sending journalists to tell both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to block Americans from our reporting and analysis with a paywall. We believe that quality journalism should be available to everyone, and paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes a difference.

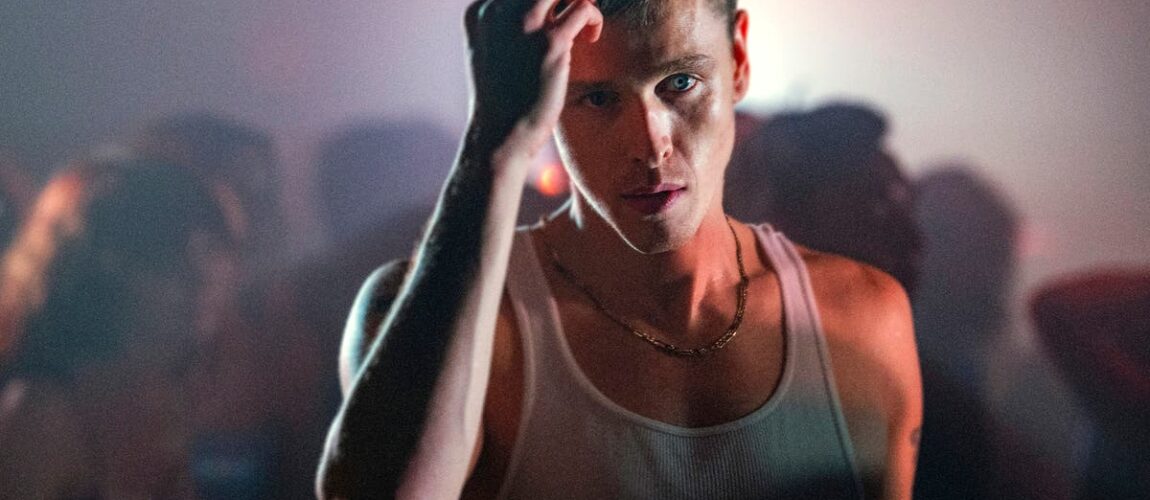

Harris Dickinson was nervous to approach Nicole Kidman.

This would not necessarily be significant under normal circumstances, but English the actor had already been cast opposite her in the erotic drama Babygirl, as an intern who begins an affair with Kidman’s buttoned-up CEO. They had a zoom with writer-director Halina Reijn, who was excited by their playful banter and confident that Dickinson would hold her own. And yet, when he found himself at the same event as Kidman, shyness got the better of him. He admitted that Margaret Qualleywho took matters into her own hands and introduced them.

“She helped me break the ice a little bit,” Dickinson said in a recent interview with The Associated Press.

On set it would be a completely different story. Dickinson may not be nearly as “brave” as his character Samuel, but in making “Babygirl,” he, Kidman and Reijn had no choice but to dive fearlessly into this exploration of sexual power dynamics, going into intimate, uncomfortable, exciting and that I can remember. The movie Božić was shot in cinemas, one of the must-sees of the year.

“There was an unspoken thing that we adhered to,” Dickinson said. “We didn’t know each other’s personal lives. When we worked and were the characters, we didn’t stray from the material. I’ve never tried to cover all of Nicole Kidman’s history. Otherwise it would probably be a bit of a mess.”

It’s a performance that reaffirms what many in the film world have suspected since his debut seven years ago as Brooklyn questioning his sexuality in Eliza Hittman’s Beach Rats: Dickinson is one of the most exciting young talents.

Dickinson, 28, grew up in Leytonstone, east London – the same part of the forest as Alfred Hitchcock. Cinema was a part of his life, whether it was Christopher Nolan’s “Batman” films at the local multiplex or going into town to see the social realist films of Mike Leigh and Ken Loach.

“Working-class cinema interested me,” he said. “The people around me who represented my world.”

Fittingly, his entry into artistic creation began behind the camera, with a comedy web series he created as a kid that he now describes as “really bad spoofs” of movies and shows of the time. But things started to take off when he started acting in a local theater.

“I remember being encouraged by that and accepting it,” he said. “For the first time I felt myself and I felt able to express myself in a way where I didn’t feel vulnerable and I felt alive and on fire with something.”

Around the age of 17, someone suggested that he try his hand at acting professionally. He didn’t even fully understand that it was a career possibility, but he went to the audition. At the age of 20, he got a role in the movie “Rats on the Beach” and, as he said, he just “continued”. Since then he has received a wide range of opportunities in large films, including “The King’s Man” and small ones. He charmed as a male model in Ruben Östlund’s Cannes-winning “Triangle of Sorrow”, an estranged father to a 12-year-old girl in Charlotte Regan’s “Scrapper”, an actor who revives an ex-boyfriend in Joanne Hogg’s “Souvenir” Part Two”, the charismatic, tragic wrestler David Von Erich in Sean Durkin’s “Iron Claw” and a soldier in “The Flash” by Steve McQueen.

But “Babygirl” would present new challenges and opportunities with a character that is almost impossible to define.

“He was confused in a really interesting way. There wasn’t a lot of specificity to it, which I enjoyed because it was a bit of a challenge for me to pinpoint exactly what triggered it and made it be,” Dickinson said. “There was a directness that unlocked a lot for me, like a fearlessness in the way he spoke, or a social unconsciousness in a way — like I didn’t fully realize that what he was saying was affecting someone in a certain way. But I didn’t make too many rules for him.”

Part of the film’s appeal is the ever-changing power dynamic between the two characters, which could change during a scene.

As Reijn said, “It’s a cautionary tale of what happens when you suppress your own desires.” She was particularly impressed by Dickinson’s ability to make everything look improvised and the fact that he can look like a 12-year-old boy in one shot and a confident 45-year-old man in the next.

Since its premiere at the Venice Film Festival earlier this year, the film has led to surprisingly direct conversations with audiences that span generations. But, Dickinson realized, that was what Reijn wanted.

“She really wanted to show the ugliness and awkwardness of these things, these relationships and sex,” he said. “That kind of seedy version and the performative version of it is much more interesting, at least to me, than the fantasized, romanticized, sexy thing that we’ve seen a lot.”

Dickinson recently stepped back behind the camera, directing his first feature under the banner of his newly formed production company. Set against the backdrop of homelessness in London, “Dream Space” is about a drifter trying to assimilate and understand his cyclical behavior.

The film, which was completed earlier this year, gave him a greater appreciation for how many people are necessary to make a film. He also began to realize that “acting is just being able to relax.”

“When you’re relaxed, you can do things that are true,” he said. “That only happens if you have good people around you: a director who creates a good environment. An intimacy coordinator that provides a safe space. A colleague at Nicole who encourages that kind of courage and performance in what she does.”

Dickinson eventually got to the point where he was able to ask Kidman questions about working with Stanley Kubrick and Lars Von Trier. But he also kept one poignant possibility between himself and his director.

“There’s a world where Samuel doesn’t even exist. He’s just some sort of device or contrivance for her own story. And I like that because it kind of means you can sometimes take a character into a very unreal realm and be almost like a deity in the story,” Dickinson said. “We haven’t discussed that with Nicole.”