Your support helps us tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to big tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it’s investigating the finances of Elon Musk’s pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, ‘The A Word,’ which shines a light on American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to analyze the facts of the exchange. message.

At such a critical moment in American history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to continue sending journalists to tell both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to block Americans from our reporting and analysis with a paywall. We believe that quality journalism should be available to everyone, and paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes a difference.

Eight years, a Chinese the mining company expanded greatly within the threatened areas World Heritage Sitewhich the local population and nature conservationists accuse of decimating the environment.

The Okapi Wildlife Reserve became a protected area in 1996, due to its unique biodiversity and large number of endangered species, including its namesake, the okapi, the forest giraffe, of which it holds about 15% of the remaining 30,000 in the world. That’s part of it Congo Basin rainforest — the second largest in the world — and a vital carbon sink that helps mitigate climate change. It also has huge mineral wealth like gold and diamonds.

The original boundaries of the reserve were established three decades ago by the Congolese government and included the area where the Chinese company is now mining. But over the years, under unclear circumstances, the boundaries have been reduced, allowing the company to operate in a plush forest.

Mining it is prohibited in protected areas, which include the reserve, under Congo’s mining code.

Issa Aboubacar, a spokesman for the Chinese company Kimia Mining Investment, said the group was operating legally. It recently renewed its licenses until 2048, according to government records.

Congo’s mining registry says the map they use came from the files of ICCN, the body responsible for managing Congo’s protected areas, and is currently working with ICCN to update the boundaries and protect the park.

The ICCN told The Associated Press that this year’s meetings with the mining registry cleared up misunderstandings about the boundaries and that the original ones should be used. An internal government memo from August, seen by the AP, said all companies in the reserve would be closed, including Kimia Mining. However, it was not clear when and how this would happen.

The document has not been published before and is the first to confirm that the current borders are wrong, say ecologists working in Congo.

Rights groups in Congo have long called on the government to rescind the Chinese permits, saying the mining ministry had illegally awarded them based on inaccurate maps.

Here are some takeaways from the AP’s report on the matter:

Contested borders

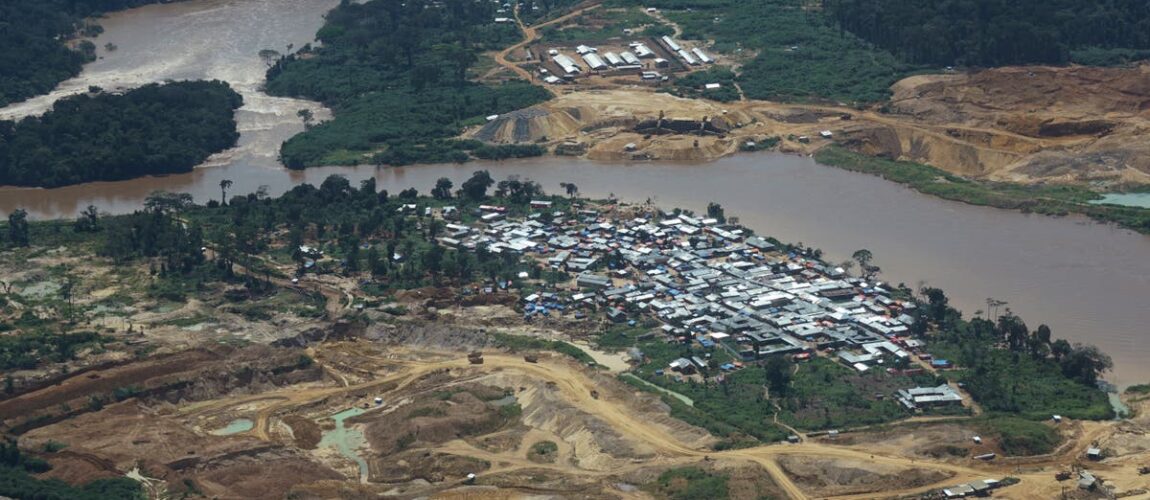

The Muchacha Mine — the largest on the reserve and one of the country’s largest small- and medium-sized gold mines — stretches approximately 12 miles (19 kilometers) along the Ituri River and consists of several semi-industrial sites. Satellite images analyzed by the AP show consistent development along the southwestern part of the reserve since it began operations in 2016, with a boom in recent years.

Joel Masselink, a geographer specializing in satellite imagery who previously worked on forest conservation projects, said the mining cadastre – the agency responsible for granting mineral permits – uses a version of the reserve’s maps that shrinks the area by almost a third. This allowed him to grant and renew exploration and exploitation concessions, he said.

The change in the borders of the world heritage site should be approved by UNESCO experts and the World Heritage Committee, who analyze the impact of the change, the spokesperson of the World Heritage Center told AP. The center said no request has been made to change the boundaries of the reserve and cases of boundary changes to facilitate development are rare.

Civil society groups in Congo accuse some government officials of deliberately moving borders for personal gain.

The UN report said the mines are controlled by the military, with some members under the protection of powerful business and political interests, and that soldiers occasionally deny local officials access to the sites.

Impact on the environment and communities

Nearly two dozen residents, as well as former and current Kimia Mining employees from villages in and around the reserve, told AP that mining is decimating forests and wildlife and polluting water and soil.

Five people who worked at Kimia’s mines, none of whom wanted to be named for fear of reprisals, said that when the Chinese end up in an area, they abandon exposed, toxic water sources. Sometimes people would fall into uncovered pits and when it rained, the water seeped into the ground.

Mining employees and experts say Chinese companies use mercury, which is used to separate gold from ore, in their operations. UN is considered one of the top ten chemicals of public health concern and can have toxic effects on the nervous and immune systems.

Assana, a fisherman who worked in the mines and wanted to use only his first name, said it now takes four days to catch the same amount of fish he used to get a day. While doing odd jobs for the company last year, the 38-year-old saw the Chinese repeatedly cutting down chunks of forest, making the heat unbearable, he said.

Between last January and May, the reserve lost more than 480 hectares (1,186 acres) of forest cover — the size of nearly 900 American football fields — according to a joint statement from the Wildlife Conservation Society and government agencies, which said it was concerned by the findings.

Double standards

Residents, who used to mine in the reserve, are angry with the double arshins.

Despite it being a protected forest, people still mined there until the authorities cracked down, mostly after the arrival of the Chinese. Kimia Mining allows local residents limited access to tailings mining areas, but at a fee that many cannot afford, local residents say.

Muvunga Kakule engaged in artisanal mining in the reserve, while also selling food from his farm to other miners. The 44-year-old said he is now unable to mine or sell produce because the Chinese do not buy locally. He lost 95% of his earnings and can no longer send his children to private school.

Some residents told the AP that there are no other options for work and they are forced to mine secretly and risk jail time.

Efforts to solve the problem

Conservation groups are trying to protect the reserve, but say it’s hard to enforce when there’s uncertainty about the legality.

“On the one hand, Congolese law clearly states that mining is illegal in protected areas. On the other hand, if a mine is operating with an official permit, then it creates confusion and it becomes difficult to enforce on the ground,” said Emma Stokes, vice president of field conservation for The Wildlife Conservation Society.

An internal memo, seen by the AP, describes talks by a joint working group between the ICCN – the body responsible for managing protected areas – and Congo’s mining registry, which was created to try to resolve the boundary issue.

The document states that it will initiate the process of stopping all exploitation in the reserve and integrate the joint commission’s agreed map into the mining registry system.

UNESCO has requested a report from Congo by February, to clarify what will be done to solve the problem.

___

The Associated Press’s climate and environmental reporting receives financial support from several private foundations, including coverage of global health and development in Africa from the Gates Foundation. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s philanthropy standards, list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.