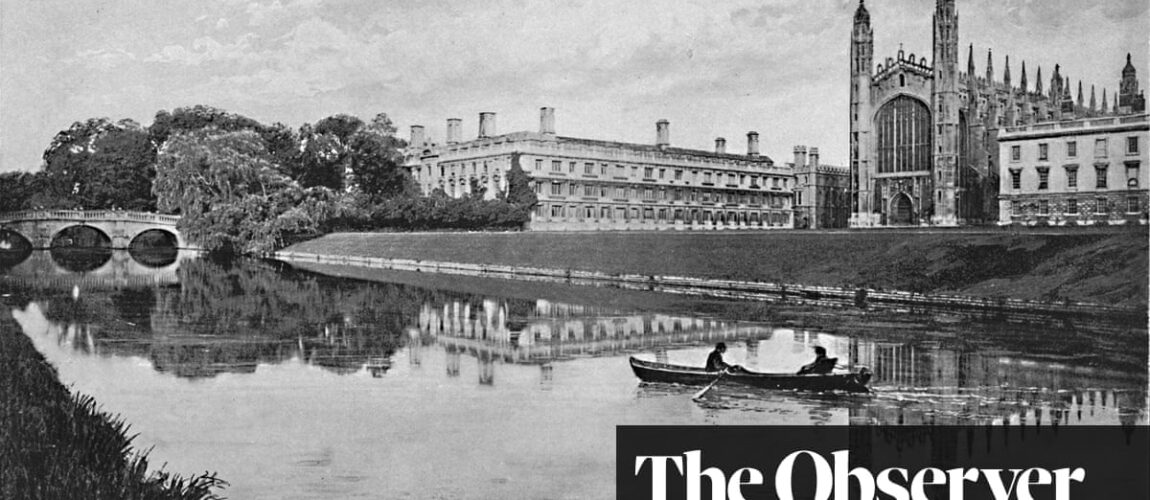

In 1561, he had granted a well-known charter University of Cambridge the power to arrest and subdue any woman “suspected of evil.” For almost three hundred years, the academy used this law to incarcerate young women workers found wandering in the dark in Cambridge.

Women were considered prostitutes and could be forcibly taken into the university’s private prison and sentenced by the vice-chancellor within weeks. More than 5,000 were caught in the 19th century alone.

Now a local historian is seeking to shed light on what happened to these women – many of whom were young – and is calling on the University of Cambridge to publicly apologize or acknowledge the injuries they suffered.

“No women ever got a fair trial, none of them even the law, according to the law of the land – there was no evidence of wrongdoing,” says author Charles Biggs. Spinning House: How Cambridge University locked women in its private prison?.

“The university did not care how they were treated. They wanted women to be removed from the streets so that they could not try anything.

When Cambridge women fell on hard times, it was easy to make money out of sex work: it was not allowed to marry dowries in Cambridge until the 1880s, and many young men had to spend any money. “Parents were very concerned that their children would come to Cambridge and be defiled by local women,” Biggs said.

In 1825, an act of parliament gave the university its own force of special police constables, nicknamed bulldogs, to patrol the town at night. The managers of the university called the officials.

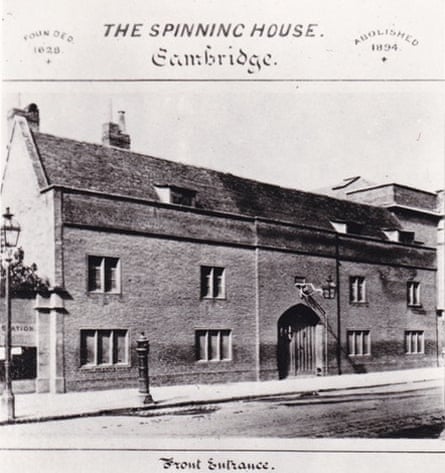

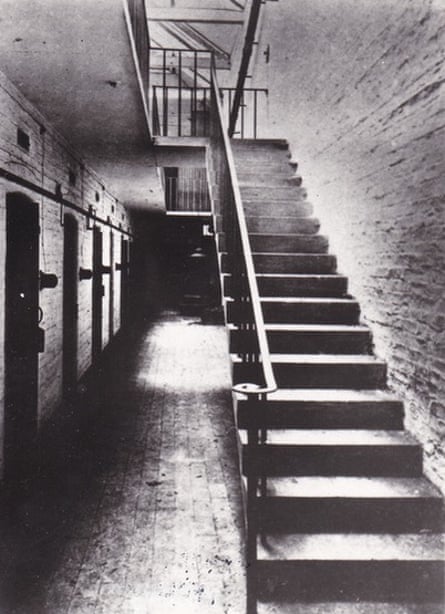

Over the past five years, I’ve been discovering what happened to women by researching university board books, along with public reports and national records. “The girls were arrested at night, to a cell in the prison, called the Spinning House, and in the morning the vice-chancellor would come and ask: “Did she come quietly? Has it come to be kind? And if it hadn’t been, if he had left with a kick, the case would have led to a longer sentence.”

Corporal punishment was also used, Biggs found. In 1748, the town’s vice-chancellor paid 10 shillings to beat “10 defiled women,” the billboards said. Prison inspectors repeatedly condemned the prison, which social historian Henry Mayhew called “an abomination” in 1851, noting that the warden would pull girls’ hair if they did not keep quiet and throw them into solitary confinement.

“The prison was notoriously cold and damp, and the food was bread and sometimes drink,” Bigg said.

In December 1846, 17-year-old Elizabeth Howe died after spending the night in a Spinning House cell with a broken window and a wet bed.

The only crime in the neighborhood was to walk with a female friend. “I was so gobsmacked when I first read the inquest about his death, I couldn’t help but notice. I wanted to cry,” said Biggs, who is giving the talk the Mill Road History Society in Cambridge this week

In another case, the councilor’s wife and daughter were stopped by the agents because they had gone before the council without consulting them. “It was a huge insult.”

The university has made more than 6,000 expulsions, with many women held several times and detained for two to three weeks at a time.

Biggs said the Spinning House was just one method the university had exercised “full control and power” over the people of Cambridge over the centuries. The university also regulated the sale of wine and spirits, the licensing of pubs and the amount of credit granted to students. Between the city and the toga was the power of Cambridge, which I think exists in some way today.

In his book, he focuses on four women who are caught in a trial of their own at the university.

In 1891, women were finally legally allowed to be accused after a national outcry about the powers and treatment of women at university. When Daisy Hopkins, 17, was caught on suspicion of “walking with a member of the university”, she was found guilty of a different offence.

His cause was established you have an important body The example is still cited today. Following the scandal, in 1894 he led Parliament to revoke the Elizabethan academy’s charter and remove the vice-chancellor’s power to arrest and imprison suspected sex workers. The Spinning House was soon demolished.

The majors would like the university to work with the city, erect a plaque in memory of the women, and hold a public exhibition about the Spinsend house and its inhabitants. “I would like the university to acknowledge that it made a mistake,” he said.

The University of Cambridge did not respond to requests for comment.