At 10.23pm on December 3rd in Seoul, I was already in bed, alternating between reading a book and watching cooking on YouTube. He was with Yoon Suk Yeol, the president; declared emergency martial law in South Korea for the first time since 1979

In an unannounced televised address, Yoon He said the imposition of martial law was “aimed at rooting out pro-North Korean forces and protecting constitutional freedoms.”

Immediately, my message boards and online chat forums lit up. What the hell is going on? Is this a joke? Can I drink at the bar at night? Can my children go to school tomorrow? What exactly is the case? The next six hours of confusion followed, until a dramatic series of events led to the end of martial law at 4.30am.

This was my first experience of military law – if it can even be called a short circuit – something I had only read about in history books until now. but even in that short time I was afraid. The experience awakened me again to the harsh and necessary reality of the Korean division. And I remembered how it can be checked and checked by our leaders to justify.

Thankfully, this time Yoon’s antics are controlled. But the martial law fiasco is a testament to both the instability and resilience of South Korean democracy. It is a chilling reminder that the dictatorship of the common trauma of the 20th century is not simply history.

However, it’s dark why? Yoon took extreme measures. Martial law is defined as temporary rule by military authorities in times of emergency when civil authorities are unable to act. Former dictators have sometimes declared martial law in response to widespread national unrest and unrest, including during the Korean War. At this time, as usual on Tuesdays, there was business; Earlier in the evening I went swimming in the public pool.

Yoon’s move comes at a time of personal and political turmoil for him. The scandal corrupted him and his family; The opposition Democratic Party just insisted on the budget bill in large parts, despite the ruling party’s protests; Yoon’s approving ratings in the 20s – all troubling, sure, but stories that don’t seem all that surprising in a relatively functioning democracy.

In his speech declaring martial law, Yoon expressed clear vitriol of his political opposition, for “anti-state activities plotting rebellion.” Most South Koreans are familiar with this insidious type of rhetoric. I grew up with this language and I still live with it, my conservative family in Busan. It’s just a reminder that there is a clear political and generational Korean-related division.

Since the founding of South Korea in 1948 and the official separation of Korea in 1953, my ancestors endured extreme poverty and constant threats from North Koreans. They painted posters of anti-communists and 16 state martial law experts, going on for several years. This history has colored their world, creating our binary and black and white lines between them, a way of fighting or flight to defend the borders or persecute others.

Like many left-leaning young Koreans, I learned to ignore and even scoff at the terrible power instilled in my grandfather’s words and more harshly. I just couldn’t see the world through an anti-communist lens. I was a teenager when South Korea embarked on the Solar Policy in the early 2000s – a more liberal approach to political containment and embracing conflict with North Korea.

“Those communist demons are to be beaten to death,” I remember hearing my hard-line conservative relatives say, referring not only to North Korean leaders, but more broadly to those who disagreed with their political views and the views of conservative party leaders. I see echoes of similar hatred and suspicions in Yoon’s speech.

Martial law is designed to suspend civil rights by extending military power. South Korean history is replete with tragedies in which martial law justified the inhumane suppression of political opposition and civil liberties. In the 20th century, many Koreans were imprisoned, tortured and killed by the state, most often under the guise of defending the country against communist enemies.

So when Yoon declared martial law, many said, “Does he think we are in the days of Park Chung-hee? of the dictators who reigned in the 60s and 70s. In a chilling historical echo, Yoon announced that media outlets would be controlled by the new martial law policy; he strikes and learns to be stopped; and whoever is arrested against this decree without a warrant.

My friends and I joked, in response, about our private KakaoTalk conversations and making certain Christmas parties not to pass curfew. We joked about how our parents, seasoned veterans of military law, had already gone to bed while the kids remained in a frenzy of fear.

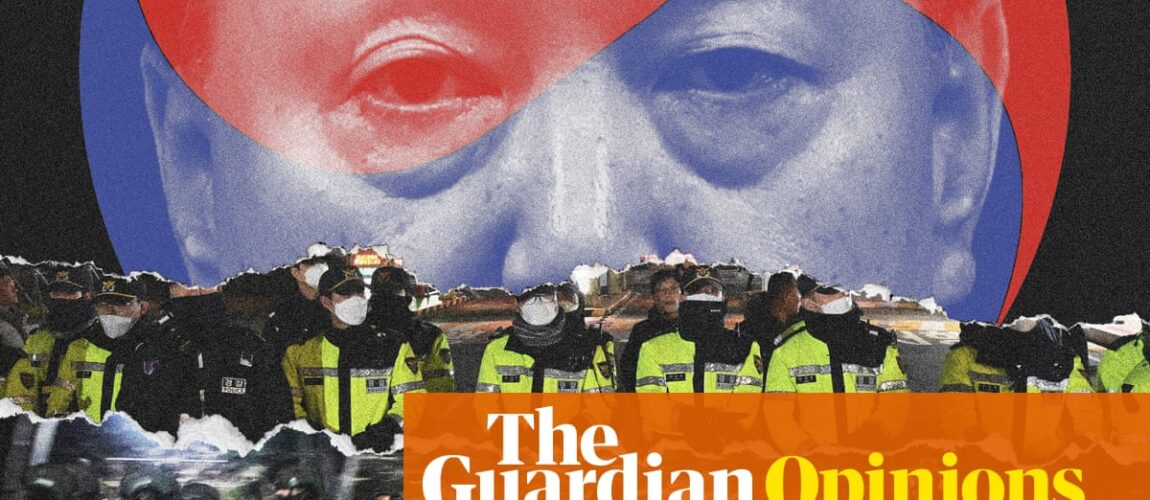

But behind Yoon’s jokes is a deep-seated historical trauma shared by millions of South Koreans, both old and young. Remembering the terror of those who lived through a decade of dictatorship. As someone who has never experienced it, I remember the terror we were told in the stories. We watched images of helicopters flying over the National Assembly and fully armed soldiers breaking windows to enter.

At this very moment, which most people have experienced, it was momentary and anxious. People are confused as to why this even happened: Yoon was never fit to support this fiasco. The president has been a lame duck since the last general election when the opposition won a landslide victory in parliament. The People’s Power Party itself did not know about Yoon’s martial law plan, and the party leader publicly condemned his decision. In rare unity, all MPs present at the National Assembly voted in the early hours of December 4 to recall Yoon’s martial law. Yoon gave in.

Uncertain what will come next for Yoon. His aides announced his resignation. Many say that this scandal is political death, illegal and a violation. The opposition is likely to begin impeachment proceedings against Yoon, possibly repeating the fate of former president Park Geunhye, the daughter of the late dictator Park Chung-hee. She was removed from office in 2017 after a corruption scandal.

South Korean democracy is still relatively young, having formally begun in 1987 with the end of the dictatorship. Yoon’s antics show that they don’t do much to destabilize the system; past trauma easily present. Yes, but it is resilience. I saw so many South Koreans flocking to Yoon quickly and fiercely. We now know that our liberties can be lost at a moment’s notice.